Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

Play the Game 2011, Tag 1

- Jens Weinreich

- 3. Oktober 2011

- 13:42

- 4 Kommentare

Die Konferenz Play the Game ist eröffnet. Über einige Highlights werde ich bis Donnerstag berichten und bin selbst in einigen Sessions eingebunden. Teilweise werden die Veranstaltungen live übertragen. Zum Beispiel diese …

[Den Livestream habe ich nach oben über die Artikelspalte versetzt.]

… und auch am Nachmittag, u.a. die Rede von Dick Pound, die inhaltlich hochwertigste, die ein IOC-Mitglied dieses Kalibers je zum Thema Korruption im Sport gehalten hat.

14.16 Uhr: Eben haben wir noch lange beim Frühstück gesessen, nun hat er seinen ersten Auftritt in Köln: James Dorsey, dessen Blog The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer ich wärmstens zur Dauer-Lektüre empfehle befehle.

15.28 Uhr: Großartiger Vortrag von Hans Bruyninckx, Universität Leuven. Kritisch, witzig, sarkastisch. Mehr dazu später.

In der Parallelgesellschaft Sport ist Verbrechen nicht Verbrechen, Korruption nicht Korruption, Doping nicht Doping … da gelten andere Regeln …

The sports world with its isolated activities is convinced of its own exceptionalism.

15.30 Uhr: Nun die Rede von Dick Pound.

The agreement that doping should not be permitted in sport is a recognition that a doped athlete is not a „real“ athlete, but an artificially-enhanced athlete. His performance cannot be compared properly with that of an athlete who has followed the agreed-upon rules and has refrained from doping.

It is a corruption of the competition caused by a deliberate action on the part of the doped athlete, all the more so because the activity is clandestine, undisclosed and intended to achieve an unfair advantage at the expense of those who have not cheated.

Doping is, therefore, a form of corruption in sport.

* * *

While not personally involved in the initiative, isolated as I am from the current IOC Administration, I thought the IOC’s decision to convoke a meeting, albeit limited and hand-picked, earlier this year was a useful first step in drawing more formalized attention to the problem of corruption in sport. I thought that the idea was good, but that it focused on the wrong issue, namely betting in sport.

It is not betting which is the problem.

I have no objection to people betting, although personally, I work too hard for my money to waste it betting on uncertainties. So, focusing on betting was, in my view, the wrong issue, even if it did get people thinking about the problem of corruption. Where corruption and betting intersect is when the normal outcome of the competition is altered by improper activity on the part of players, officials or third parties and the knowledge of such improper activities and the likely or potential impact on the outcome of the competition is used to influence the particular bets which are made.

It is still, however, not the betting as such which is the problem, but the underlying corruption of the result of the competition. Betting is simply a manner of monetization of the corruption. Betting patterns can be a useful diagnostic tool, which may indicate that corruption has occurred and, for that reason, monitoring of betting activities, and certain betting patterns is likely to be a good investment in eventual reduction or elimination of corruption.

* * *

The most disappointing aspect for me about the IOC initiative was the response of many of the sports officials involved. Instead of focusing upon the problem of corruption, many of them saw the meeting as an opportunity to advance the proposition that, because betting agencies have a profitable business in relation to sports events, the betting agencies should share those revenues with the sports organizations.

Quite properly, the betting agencies perceived this as little more than a money-grab by the sports organizations, rather than a serious effort to address the underlying problems.

Just as they have a tendency to do so with respect to doping, sports organizations tried to lay-off the problems of corruption on governments and government agencies, all but absolving themselves from any responsibility in relation to their own sports.

* * *

To make its message more compelling however, the IOC will first have to drive change within the sports organizations. It will have to develop a comprehensive plan to combat corruption in all its forms. It will have to analyze which actions can be taken by sport, which by governments alone, and which on a shared basis. It will then have to convince sports authorities that they must buy into their own responsibilities and make meaningful efforts to respond to these responsibilities before they can hope to convince governments of the importance of their involvement in the whole process.

It will not be persuasive, as it is not persuasive in the case of the fight against doping in sport, that the necessary activities are expensive. If sports authorities are not prepared spend whatever is required ensure the integrity of sport, they will inevitably bear the consequences of this neglect.

* * *

Having headed up the IOC’s independent investigation of the Salt Lake City bidding scandal in 1998 and 1999, I am all too aware of the ability of the media to draw attention to and to influence public perception of the conduct of an organization and that of its members. The amount of media attention focused on the IOC during this period came close to destroying the organization itself.

It was only our ability to demonstrate that we took the situation seriously and that we were determined to fix the problem which, in the end, saved the day.

When I compare that firestorm of media attention to the relatively benign, again with certain exceptions, treatment of the extraordinary conduct of FIFA and certain of its executives, I am astonished. This is a far more serious and far more extensive problem for the world’s most popular sport than the relatively narrow conduct, improper as it was, of a few IOC members.

* * *

In my respectful opinion, FIFA has fallen far short of a credible demonstration that it recognizes the many problems it faces, that it has the will to solve them, that it is willing to be transparent about what it is doing and what it finds and that its conduct in the future will be such that the public can be confident in the governance of the sport.

At the moment, I do not believe that such confidence exists or would be justified if it did.

* * *

Sport, while not alone in the need for good governance, has been particularly deficient, especially with respect to transparency. Indeed, more than most organizations, sport has vigorously resisted any suggestion that its governance should be transparent and that the results, financial and otherwise, of its activities should be audited and disclosed.

It is all very well to say that sports organizations are private and that there is no need to disclose such information.

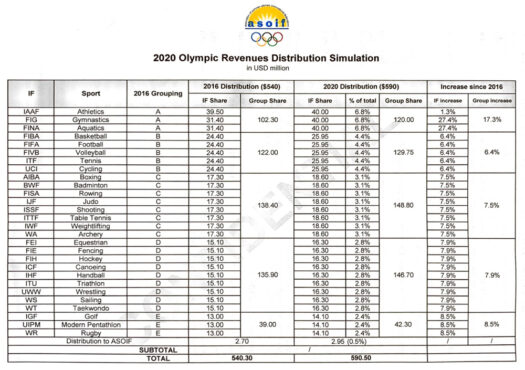

The fact of the matter, however, is that all sports organizations depend to some degree on public funds and funds provided by the public in the form of ticket revenues, sponsorships, television revenues and the use of facilities constructed wholly or partially with public funds. In many countries, the national federations affiliated with international federations depend in large measure upon government support for their activities.

It would not take too much imagination to consider the possibility, as part of government responsibility in matters of corruption in sport, for them to require disclosure of such information as a condition for any activity on the part of national or international federations in that country.

* * *

Not to be overlooked in any consideration of fighting corruption sport would be the possible range of actions on the part of sponsors.

Some argue that cycling would never have begun a serious fight to eliminate doping in its sport had some of the team sponsors not walked away from their sponsorships, or failed to renew their sponsorships.

If I were providing professional advice to potential sponsors of sporting events or sport organizations, I would be sure to advise them to insist upon anti-corruption provision in the contract, which would allow the sponsor to withdraw at anytime if corruption occurred and to recover any amounts paid in respect of the sponsorship, plus amounts incurred by the sponsor in activation of the sponsorship.

* * *

Remember that if sponsorship disappears from organized sport, organized sport disappears from the face of the planet.

Organized sport, particularly professional sport, depends on private sector support, not government support. The private sector is, therefore, in a position to insist that any organization it sponsors be free of corruption.

* * *

If we want sport to go the way of the World Wrestling Federation, which could no longer even pretend that what it delivered was sport, and changed its name to World Wrestling Entertainment, which delivers programming ranking somewhere between a circus and a farce, all we have to do is keep going in the direction in which we have allowed sport to drift over the past decades.

Und wie er mir zuvor bereits gesagt hat:

Well, if I wanted to do a serious and credible job, I would be sure to have at least some non-FIFA people on the commission. I would also ask for some law enforcement assistance. I would also make the terms of reference public, to demonstrate that I was serious. I would also set up a mechanism to permit anyone with knowledge to provide it, even on anonymous basis, if necessary.

Samaranch chaired our Reform Commission, but did not sit on my ad hoc Investigation Commission. If I were Blatter, I would do the same. We also had outsiders on that Reform Commission, in addition to IF and NOC representatives, so it might be wise to have some NFs on the FIFA Commission.

16.07 Uhr: Nun William Gaillard, UEFA, Platini-Berater.

Pingback: Play the Game - Tag 1 (Liveblog) - Korruption und Wetten | Daniel Drepper

Richard Pounds komplette Rede via PTG

Wäre interessant zu erfahren, wie sich hier die deutschen Sportmedien en detail einordnen lassen. Gefühlt, scheint es ähnlich zu sein.

Pingback: Sportblogger auf der DLF-Konferenz: Zwischen Chance und Perspektivlosigkeit | take56