Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

Child athletes are too valuable for the Olympic system to set age limits

- Jens Weinreich

- 25. Februar 2022

- 23:51

- Keine Kommentare

The Olympic Games thrive on high-performing children – some of them so young that they are not even allowed to compete in the Youth Olympic Games. Jens Weinreich discusses why it is so hard for Olympic sports federations to set age limits and shows how it leaves child athletes vulnerable to authoritarian states chasing medals and sport glory. (First published by Play the Game)

The doping case of Kamila Valieva has raised questions about a minimum age for Olympic athletes. Again. The age rules are defined very differently in the seven Olympic winter sports federations. It is no different among the summer sports federations. Age regulations sometimes differ even within these federations, depending on the sport, discipline, or gender. In the International Skating Union (ISU), a proposal to raise the minimum age in figure skating from fifteen to seventeen years failed most recently in June 2018. Of course, at the ISU congress at the time, the Russians also voted against this proposal.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) introduced the Youth Olympic Games (YOG) at its 2007 Session in Guatemala. Why are there these global competitions called YOG, when at the same time children participate in – how shall we say: real – Olympic Games? Why is there so little coordination? Why has not even the IOC, as the sole owner of these circus events, reminded us of these Youth Games in the bitter discussions of the past weeks?

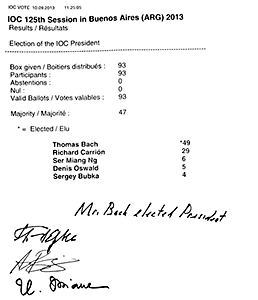

Some answers to these questions are: Because there are no clear, plausible age rules. The rules have been interpreted and changed for ages to suit the needs of the moment. And so, when – as in the case of Valieva – the whole world watches children obviously being abused as human material by medal scoundrels, then crocodile tears flow. Then the IOC president Thomas Bach, whose marketing department also turns children’s high-performance sport into money, talks about the values and lack of empathy of Kamila Valieva’s coach Eteri Tutberidze and the entire entourage.

Some thoughts on competitive sport in totalitarian systems

Before I go into the question of age limits in more detail, I would first like to express some thoughts on competitive sport in totalitarian systems. Because one is definitely related to the other.

According to everything that is known about Russian competitive sport, the state doping system around the irregular 2014 Winter Russian doping Olympics in Sochi and precisely the regime of Eteri Tutberidze, this perfectly meets the definition of a totalitarian system. What did Dmitry Peskov, the spokesman for Russia’s eternal president Vladimir Putin, say the day after the girls‘ and women’s figure skating competition in Beijing?

„Everyone knows that this toughness is the key to victory in elite sport.“

And what did Russia’s deputy prime minister Dmitry Chernyshenko, the CEO of the organising committee of the irregular 2014 Sochi Olympics, say?

The Olympic Games are the „pinnacle of professional sport“ for all athletes. „Every single athlete bears the hopes and dreams of their entire nation for their success. That is a known pressure, and it is also what drives them forward, with a fighting spirit.“

Perhaps I may say at this point that I grew up in a totalitarian state where such words were part of the state doctrine. In a small state called the German Democratic Republic (GDR) that was enclosed by walls and fences made of barbed wire and that put on an incomparably gigantic performance at the Olympic Games. That performed on a par with the superpowers USA and Soviet Union, winning the medal table once at the Winter Olympics (1984 in Sarajevo), twice finishing second at the Summer Games (1976 in Montreal, 1988 in Seoul) – both times behind the Soviet Union, whose collapse Vladimir Putin once described as the greatest tragedies of the 20th century.

Propaganda slogans like those we have heard from Russian but also Chinese officials lately were drilled into me in my childhood and youth and in my first years as an adult. So on that day, when the nomenclature cadres Peskov and Chernyshenko, the loyal servants of their lord and master Vladimir Putin, defended the brutal coach Tutberidze and demanded toughness from skating children, I had to think of Marita Koch. She was one of the heroines of my childhood in the GDR, who celebrated her 65th birthday exactly on that day.

The world star who was not allowed to stop

Marita Koch was a world star. She set fifteen world records in Olympic disciplines. She became an Olympic champion. She was the victim of an Olympic boycott. She was World and European champion. She has held the world record in the 400 metres since October 1985 in Canberra – 47,60 seconds. It is the second oldest world record in athletics and will probably last for all eternity. Marita Koch was awarded the title of „World athlete of the year“ three times.

She was doped, like thousands of other GDR athletes – and thousands of other Olympic athletes from all over the world since then.

The allegedly doped 15-year-old Kamila Valieva and Marita Koch are one and the same side of the coin. Both come from totalitarian Olympic systems from which there was and is no escape.

The Olympic system, indeed this whole industry, is based on such totalitarian systems – and it is to a large extent itself a totalitarian system, as we see with the IOC and with almost all Olympic federations.

Such systems have existed for decades. Just like Kamila Valieva, Marita Koch was also a victim at some point when doping began. And even as a star and Olympic champion, it was almost impossible for her to escape this system. I don’t want to defend Marita Koch, but I would like to describe a process that illustrates how this system dominated at all levels.

After the world record in Canberra in 1985, Marita Koch wanted to end her career. She was 28 years old. She wanted to focus on her studies. She was tired. She wanted a child.

But Marita Koch was not only a world star – she was a super star in the GDR, a reliable heroine in the production of medals and records. They had other plans for her. They had other orders for her. So, the GDR sports dictator Manfred Ewald forbade the grown woman to have a child and end her career.

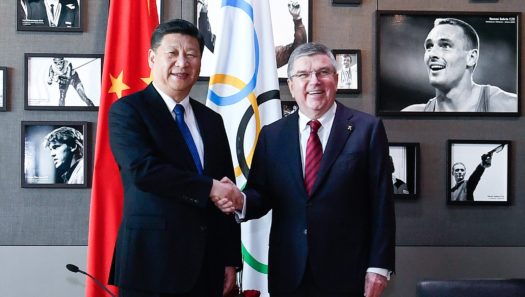

Instead, Ewald wanted Koch to continue until the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. Erich Honecker, Head of State and Chairman of the Communist Party had already promised IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch that the GDR would participate in the next Olympic Games. This was one of the reasons why Samaranch presented him with the Olympic Order at the 1985 IOC session in East Berlin; the same Order with which Thomas Bach adorned China’s State and Party Leader Xi Jinping.

In Seoul, the first Games after the two big boycotts of Moscow (1980) and Los Angeles (1984), the GDR wanted to take first place in the medal table. That was Ewald’s dream. That was the party’s order. That was the plan.

Many years ago, I found a handwritten letter from Marita Koch in the archives of the communist party (SED) and the GDR Sports Federation after the archives were opened to the public after the German unification. I don’t know if the letter I am quoting from here, and which I handed over to Marita Koch myself years ago, was ever published. In January 1986, she had sent this letter to the regional party leader of Rostock county, where she lived, asking him for support.

In it, Koch offered two things: First, she declared her willingness to give a propaganda speech at the upcoming communist party congress in East Berlin; second, she declared her willingness to still participate in the 1986 European Championships in Stuttgart. In return, however, she asked the party leadership, the Politburo, to assert itself against the sports chief Ewald (who in turn was a member of the extended party leadership).

The sports chief Ewald had threatened Koch, saying „I don’t want European championship titles, I want Olympic victories.“

A small excerpt from the letter Koch wrote. It translates: I should decide, either until 1988 or … (not pronounced). He doesn’t want European championship titles but Olympic victories. We were both very disappointed about comrade Ewald’s attitude. All the reasons we gave, such as wanting children, studies, health reasons, etc., he found more or less insignificant.

Ewald demanded obedience. If Koch did not follow his instructions, she would lose all the privileges she had earned with her many successes, and then she would no longer be allowed to study.

„My desire to have children and my health problems were immaterial to him“, wrote Marita Koch.

Koch prevailed but underage athletes do not have a chance

In this one big conflict, the last of her sporting career, Koch prevailed against the sports supremo. She took part in the 1986 European Championships. She won two gold medals in Stuttgart – in West Germany, that was particularly important. That had additional symbolic power.

Marita Koch fulfilled the plan others had made for her. She was an obedient sportswoman. And she was lucky enough to have advocates in the Politburo of the communist party who allowed her to end her career.

Once again: Marita Koch was a world star. She had already achieved everything. What do you think would have happened to a 20-year-old, or even an underage athlete, who defied the instructions of the sports and party leadership and the medal requirements for the current Olympic cycle?

So, to get back to 2022: What would happen to kids like Kamila Valieva who defied instructions from those around her? Or what would happen to Chinese sport minors, earmarked for gold medals by the communist party and sports leadership, who suddenly want to go their own way, a self-determined way?

That doesn’t work in totalitarian Olympic systems.

Incidentally, in 1986, when Koch had to fight to end her career, the IAAF (which is now called World Athletics) held a World Junior Championships for the first time. In Athens. Of course, the GDR was the most successful nation, as it was at the second World Junior Championships in 1988 in Sudbury, Canada.

And now please guess which are the most successful nations by a huge margin at the Youth Olympic Games?

China and Russia.

Do you see any patterns there?

The IOC Executive Board could but will not institute age limits

I now return to the question of an Olympic age limit or minimum age. So far, the Olympic Charter, the basic law of the IOC and the Olympic Games, does not specify a minimum age for athletes. Rule 42 only says:

„There may be no age limit for competitors in the Olympic Games other than as prescribed in the competition rules of an IF as approved by the IOC Executive Board.“

So all power lies with the Executive Board, yet again. If Bach’s closest and most powerful fellows were to exercise this power, as it is constantly done on other issues, international federations such as the ISU could have the thumbscrews put on them relatively quickly.

What should be more important than protecting children? The IOC Executive Board decides on the composition of the Olympic programme, recently it even awards the Olympic Games (as we have seen with Brisbane 2032) and the Olympic Youth Games. The IOC session only blesses the decisions of the Executive Board.

Unlike the Olympic Games, there are age restrictions at the Youth Games: Here participants must be at least 15 years old in the year of the respective Games, but no older than 18. From this point of view, it would be logical to introduce an age limit of 18 for the Olympic Games and make it for adults only. For all those between 15 and 18, there would be the Youth Games.

But this will not happen.

The Olympics thrive on high-performing children

The IOC will never deny minors participation in the Olympic Games. The fact will remain that in many sports, children are too young for the Youth Games, but old enough for the Olympic Games. The best example: at the 2021 Olympics in Tokyo, when skateboarding celebrated its Olympic premiere, the medallists Momiji Nishiya from Japan (gold) and Rayssa Leal from Brazil (silver), who were only 13 years old, were also celebrated by the IOC and president Thomas Bach. The absurdity that Nishiya and Leal were too young to take part in the Youth Olympic Games was studiously overlooked.

The truth is that large parts of the media and the sport science world play along with this game. That was the case last year when Nishiya and Leal and the other children skateboarders had their big moments. It was no different in Beijing at the team competition in figure skating, when Valieva enraptured with an impressive performance – only the news of the positive doping test changed the coverage enormously.

Olympic history thrives on children’s high-performance sport. In the marketing machinery of the IOC, the many negative and even criminal aspects inevitably associated with it are almost completely ignored. Many stories of underage prodigies are among the myths of the Olympics and have been sold as such for decades.

The Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci was fourteen when she won her first three gold medals in Montreal in 1976 and for the first time ever received the then highest score of 10.0 for her performance on the uneven bars. Comaneci’s coach was the notorious Béla Károlyi.

The US American Michael Phelps, who won 23 Olympic gold medals, first competed in the 2000 Sydney Games as a fifteen-year-old. His teammate Katie Ledecky won her first of seven Olympic gold medals as a fifteen-year-old in London in 2012.

And Kornelia Grummt-Ender, at thirteen, is the youngest German Olympic participant of all time. She won three medals in 1972 in Munich in GDR kit. Four years later, in Montreal, she became a four-time Olympic champion. She won two gold medals within half an hour – in the 100-metre butterfly and 200-metre freestyle, both with world records.

In fact, the term Wunderkind is used constantly by IOC’s marketing trumpeters. If you look at the IOC websites, for example for the 2020 Winter Youth Games in Lausanne, there is talk of the Freeski Wunderkind Eileen Gu and the Russian Skating Wunderkind Daniil Samasonov, the latter also a protégé of Eteri Tutberidze. There is a video about the underage figure skaters, especially the Russians, which says: „All eyes are on the future generation of figure skaters. Next Stop: Beijing 2022.“

That’s how it works. This is another reason why crocodile tears from IOC bigwigs should be taken with a grain of salt.

Youth Olympic Games – a business decision

The introduction of the Youth Olympic Games in 2007 at the IOC session in Guatemala was above all a business decision of principle. For in the Olympic core markets, the clientele was threatening to become senile. The Olympic Games as a product worth billions were to become more modern and more attractive for young sections of the population – the YOG were also created for this purpose.

Only one IOC member objected to the plans at the time: It was, as so often, the Canadian Richard Pound. At the time, he was also President of the World Anti-Doping Agency WADA, he had been an Olympic swimmer himself as a teenager and knew about certain dangers.

While Pound was the only one to seriously argue against the introduction of YOG, the then Croatian IOC member Antun Vrdoljak declared that the children and grandchildren of IOC members should automatically be allowed to participate in the Youth Games. So much for the level of discussion among those who help decide the fates of hundreds of thousands of underage high-performance athletes.

Dick Pound, by the way, decided to stay away from the first YOG. Summer Youth Olympic Games have so far been held in 2010 (Singapore), 2014 (Nanjing) and 2018 (Buenos Aires), with the next to be held in Dakar, Senegal in 2026. There were Winter Youth Games in Innsbruck in 2012, Lillehammer in 2016 and Lausanne in 2020. In 2024, it is the turn of Gangwon Province in South Korea where the 2018 Winter Olympics were held, again with the two centres PyeongChang and Gangneung.

As I mentioned earlier, if one looks at the overall YOG medal table so far, one thing stands out: China (187 medals, 99 of them gold) and Russia (228 medals, 96 gold) lead the ranking by a huge margin. Two of those nations, in other words, in which the training of minors is brutally promoted by the state.

The IOC, however, sells its Youth Olympic Games as a unique values factory that is not only about sport but about Olympic education. In fact, the Youth Games have become in large parts a laboratory for the real Games. 3×3 basketball, sport climbing, skateboarding and breakdancing were tested at the Youth Games – and then entered the Olympic programme. Breakdancing will be held for the first time in Paris in 2024.

The increasing professionalisation of junior sport

In winter sports, World Junior Championships have been held almost continuously since the 1970s and 1980s. Parallel to the introduction of the Youth Olympic Games, the last Olympic federations introduced junior world championships in summer sports. Thus, under the umbrella of the IOC and its YOG, along with the continental Youth Games, junior sport was further professionalised worldwide.

Some summer sports federations had junior world championships for many decades, such as fencing (already since 1950, a record among professional federations), rowing (1967), weightlifting (1975) or athletics (1986). The world swimming federation FINA only started its youth world championships in 2006. In 2015, however, FINA let ten-year-old Alzain Tareq from Bahrain swim in the adult world championships. Topsy-turvy world – absurd Olympic rules.

The point is, as always in the Olympic sector: the IOC and also the continental umbrella organisations of the NOCs have created a new reality with the YOG and with these continental offshoots. Everything is geared towards this: The policies of the NOCs, the sports federations (national and international) and later also by the funding from politicians and governments with tax money.

You can see very clearly how sceptical some federations and NOCs were about the first YOG. Even at some of the junior world championships that were introduced most recently: In swimming, for example, the Australians did not participate in the first Junior World Championships.

Such well-founded scepticism is soon overruled by the fait accompli. The YOG and junior championships will be absorbed by the system, and resistance will eventually be a thing of the past. In the process, the problems remain the same, nothing is solved. But they march on, all in a row. That’s how it always works.

The campaigners against raising age limits or even an Olympic minimum age of 18 often use the argument about different requirements in different sports and disciplines. That may be true to some extent. But there is one thing that stumps all arguments: Olympic excellence requires several thousands of hours of training work. The emphasis is on work. This can be quantified very precisely for each sport.

And that is why this formula applies to all sports: the lower the entry hurdles, the lower the minimum age, the greater the certainty that children as young as pre-school age will be subjected to a dangerous, externally determined Olympic mechanism, as the Valieva case impressively proves. As we all know, as the many revelations about abuse of protégés in sport in recent years have shown, all the huge scandals, this does not only apply to totalitarian social systems.

Sie wollen Recherche-Journalismus und olympische Bildung finanzieren?

Do you want to support investigative journalism and Olympic education?

SPORT & POLITICS Shop.

Subscribe to my Olympic newsletter: via Steady. The regular newsletter is free. Bur you are also free to choose from three different payment plans and book all product at once!

-

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 39,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 39,90 € -

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 19,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 19,90 € -

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 29,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 29,90 € -

Angebot Produkt im Angebot

Business-Paket

Business-Paket1.090,00 €Ursprünglicher Preis war: 1.090,00 €690,00 €Aktueller Preis ist: 690,00 €. -

Angebot Produkt im Angebot

„Macht, Moneten, Marionetten“ E-Book

„Macht, Moneten, Marionetten“ E-Book19,90 €Ursprünglicher Preis war: 19,90 €9,90 €Aktueller Preis ist: 9,90 €. -

Angebot Produkt im Angebot

Classics „Korruption im Sport“

Classics „Korruption im Sport“19,90 €Ursprünglicher Preis war: 19,90 €7,90 €Aktueller Preis ist: 7,90 €.