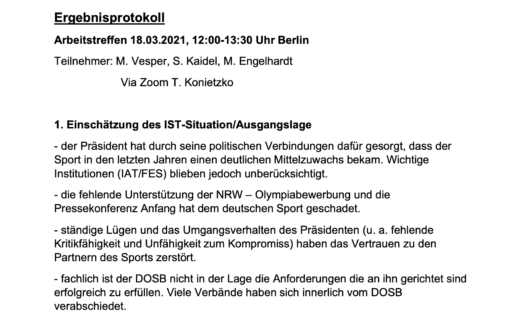

Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

The story behind the story of Russia, Doping, WADA and the IOC

- Nick Harris

- 27. Juli 2016

- 12:18

- Ein Kommentar

Meine Kollegen Martha Kelner und Nick Harris haben im Juli 2013 in der „Mail on Sunday“ erstmals über die großflächige russische Doping-Verschwörung berichtet. Sie hatten die Aussagen von einem Dutzend russischer Whistleblower zusammen getragen. Doch bis zur ersten ARD-Dokumentation im Dezember 2014 passierte: nichts. IAAF? Totenstille. WADA? Totenstille. IOC? Büro-Mikado. Ich hatte eigentlich vor, die Geschichte dieser Enthüllung selbst aufzuschreiben, nun ist mir Nick zuvor gekommen, umso besser. Hier sein Beitrag:

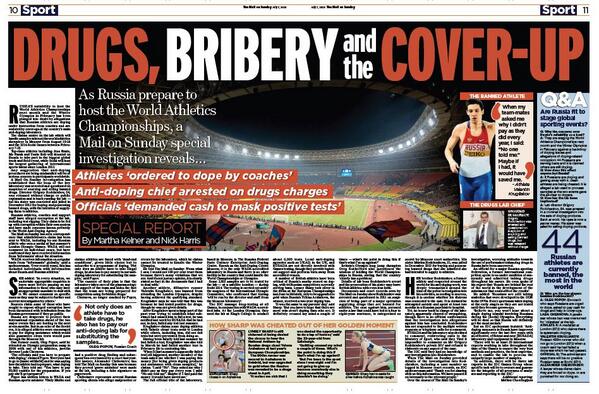

Mail on Sunday, Juli 2013

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was aware Russia ran a state-sponsored doping programme in which the head of that nation’s WADA-accredited lab was a central figure as long ago as the first week of July 2013.

I know this because I told them.

I told them on the phone and then I told them in writing.

They acknowledged this was new information to them and they asked for more, which was provided. This piece will include proof of that, in detail, in a moment.

The IOC then said they had ‘passed it on internally to the relevant people and we will get back to you as soon as we get a response.’

They never did get back to me. Apparently they did nothing at all with that information, some of which was utterly extraordinary. For example: we uncovered the fact that the head of the corrupted lab, Grigory Rodchenkov, had been arrested in 2011 for alleged involvement in a doping ring, along with his sister.

While in custody and terrified of shameful exposure, Rodchenkov made a grizzly suicide attempt and was committed by the Russian authorities to an asylum for more than two months.

His performance-enhancing drug-dealing case was assigned to a secret court. Records of that case then ‘disappeared’. His sister was initially sent to prison, then released.

Rodchenkov was privately freed to go back to work at the Moscow lab to oversee the systematic doping corruption of major events including the 2014 Winter Olympics in Russia.

The IOC said they had no knowledge of Rodchenkov’s wrong-doing, arrest, asylum trauma or return to work for corrupt purposes when informed about it in July 2013 – or three years ago, in other words. But when they were given that information they chose to ignore it, apparently.

In doing so, they allowed the Sochi Olympics – the Olympics of which they are guardians – to be corrupted, despite further specific warnings in a series of national newspaper articles that Russia would corrupt the Sochi Games. The IOC let state-sponsored doping flourish.

Extremely belatedly, after two investigations by the world anti-doping agency (WADA) showed Russian state-sponsored doping to be a fact (something WADA were told about in 2012, and again in 2013, at the same time as the IAAF, the world governing body of athletics, details also to follow below), the IOC had a decision to make over whether to let tainted Russia take part part in second Olympics with the IOC’s full knowledge of the problem.

Yesterday the IOC said Russia was good to go, in effect. Fit for Rio. Despite a mountain of hard evidence about a long-standing, wide-ranging endemic doping problem across Russian sport, the IOC decided not to put a blanket ban on Russia at Rio 2016.

This is not an opinion piece.

You may believe athletes who use banned drugs are a scourge on sport, a stain that needs to be removed. Or you might not be that bothered. That’s entirely your prerogative.

But this is the story behind the story that has become the major sports scandal of 2016, and arguably of the past decade. And it should demonstrate which of the positions in the paragraph above are held by the powers that control global elite sport.

As regular readers of my website Sportingintelligence and followers of this website’s Twitter and Facebook accounts know, after starting this website, I subsequently also became the chief sports news correspondent of the Mail on Sunday.

It was in that role that myself and my colleague Martha Kelner first broke the news in July 2013 of the Russia doping conspiracy centred around the tainted Moscow WADA lab and its director, Rodchenkov (and there is a BBC profile of him here).

For those unaware of the Russian scandal the details in a nutshell are this: hundreds of sportspeople from many sports were provided with banned performance-enhancing drugs over many years.

This was often done by coaches, with the support of governing bodies, and in the knowledge of senior figures meant to prevent doping – including officials at the Russian sports ministry, the Russian anti-doping agency, and the WADA lab controlled by Rodchenkov.

Our story ran on the weekend of 7 July 2013.

Not only were the sportspeople allowed to dope, and encouraged to dope, but they were also protected if they tested positive; their samples were corruptly recorded as clean. And, in some cases, athletes who were clean had their clean samples tainted to become positive so that favoured dirty athletes were given preferential access to certain major sports events instead of them.

It goes without saying this is a simplified version of events. But it was state-sponsored doping, authorised and effectively rubber-stamped by Russia’s government, by president Vladimir Putin, and by a variety of his political appointees. WADA’s most recent McLaren report about the matter is here.

It is increasingly difficult to comprehend why the IOC, WADA, the IAAF and other major bodies opted to ignore evidence of systematic wrong-doing. Alternatively it is easy to comprehend, if you conclude that actually they don’t really care about doping as long as the dollars continue to flow.

But this isn’t an opinion piece. It’s the story behind the story. So let’s start at the beginning.

The investigation

As summer 2013 approached, Russia was preparing to stage the 2013 world athletics championships in Moscow.

It was no secret to anyone that Russian track and field had a problem with performance-enhancing drugs, not least because it routinely topped the IAAF tables for banned athletes at any one time.

In this context, Martha interviewed British long-jumper Greg Rutherford in May 2013 for an article in the MoS in which he questioned the suitability of Moscow as a host of the blue ribband event for athletics.

In response to that article, Martha was contacted by a Russian athletics coach, Oleg Popov, who said he shared Rutherford’s concerns. In fact, he said, he was desperately worried that his country, Russia, had been running an institutional doping programme in athletics for a number of years, and that the scandal needed to be exposed. He had evidence, and compatriots who would back him up, he said.

Martha is a brilliant young journalist, the SJA Young Sports Writer of the Year for 2012, and now, in summer 2016 and still in her early 20s, about to head to Rio as the athletics correspondent for Associated Newspapers.

In Spring 2013, she was not completely sure how to handle a random response from a Russian stranger about what sounded like amazing claims about doping. She talked to Popov via email, then Skype, fortuitously with the help of a Russian-speaking work experience intern.

Martha later wrote about Oleg Popov’s role in our investigation but suffice to say, once she’d shared his initial correspondence with me, we thought it was worth investing at least a few days in following it up.

In fact, after putting together a comprehensive ‘to do’ list, we spent nearly two months on the next phase, directing our research from the UK but working with colleagues and contacts in Russia and further afield. Oleg put us into contact with others, who in turn opened more doors.

Investigative journalism can be a long, painstaking process with no guarantee of reward but over the weeks we gathered tens of thousands of words of testimony from coaches, athletes, lawyers, support staff, independent witnesses and whistle-blower insiders, some of whom to this day must remain anonymous.

Next we collected corroboratory paperwork from anyone who could provide it; emails and letters and positive or negative drug sample documents; expert opinion on technical aspects of these documents, audio of various hearings and all sorts of court files.

Then we tried to double-source everything to see if it was true, or might be true, or could be proved to be false. And then we began the long and frustrating process of seeking official comment from all those implicated in wrong-doing (most of whom refused to respond), and last of all putting all of our findings to the IAAF, to WADA and the IOC.

Our story named some of the people who helped up as witnesses, and protected the identities of others. But the tale was clear: while we focussed on the imminent threat of corruption at the Moscow world athletics championships of 2013, there was a problem across Russian sport.

One senior Russian winter sports official even lamented Russia wasn’t as good at doping as in the past but said he knew the corrupt system would guarantee Russia most medals at Sochi 2014 and cover up what needed to be covered up. He told us:

‘Russia doesn’t produce the doping substances used in sport now. Everything is imported from Moldova, two factories, Ukraine, Turkey, India, Singapore, and China. The most common one is Moldova.

‘If you want to buy [drugs] cheaper you should go to the Kiev railway station at 4 am when a train from Chisinau arrives and to see what’s happening there as most of the people coming by this train bring steroids for sale …

‘Believe me you won’t hear about a single doping scandal involving Russian sportsmen during the [Sochi] Olympics … everything will be done so that Russia will definitely get the most medals.’

Perhaps the most dramatic individual story among many we gathered was that of Rodchenkov, then 54 and resident in Moscow, still working, now 57 and living in exile in the USA.

One of our sources shared with us a letter sent by a Russian athlete to WADA in 2012, naming Rodchenkov’s sister, Marina Rodchenkova, as a key figure alongside Rodchenkov in a 2011 doping conspiracy involving senior (named) Russia athletics officials.

Marina was jailed in 2012 for possessing performance-enhancing drugs with intent to supply in 2011. Back in 2011, Rodchenkov too was arrested as part of the same conspiracy, after a tip from clean athletes.

Secret paperwork we obtained indicated he was diagnosed with a severe depressive condition around that time and attempted to take his own life on 23 February 2011. Different sources varied on the method but it was clearly a serious attempt; one claimed he tried to disembowel himself while another said he slashed his wrists. In any case, in a confidential appeal memo he later wrote himself, he confirms he tried to kill himself and that he was sectioned to a mental hospital until 26 April that year before before being released. No charges followed and he was sent back to work.

We can only speculate on the precise conditions of his release. We made numerous attempts to contact Rodchenkov by phone, email and in person in summer 2013 and he consistently, politely declined to comment, or to confirm or deny anything.

But in a May 2016 interview with the New York Times, he hinted that he expected to be jailed for dealing drugs back in 2011 but said he believed he was sent back to work to deliver the Sochi cover-up the Russian authorities wanted.

As the NYT reported:

‘He suspected that he had been spared punishment so that he could play a crucial role at the Sochi Games.’

He told the NYT:

It’s my redemption: success in Sochi. Instead of being in prison, win at any cost.”

Back in 2013 our investigation managed to establish that, initially at least, a criminal case was lodged against Rodchenkov in the Russian courts, case number 44y-0173/2012, relating to a criminal investigation under clause 234 (3) of the Russian criminal code, which dealt with supply of banned drugs.

But access to details was impossible to obtain and we were told case details were forbidden. In effect, the case had been ‘disappeared’ from public view.

The upshot was we had a mass of first-person testimony alleging a large-scale doping system across Russia sport, involving Rodchenkov and his lab, aided and abetted (and sanctioned) by a range of official bodies including but not only the anti-doping agency of Russia (RUSADA) and the sports ministry, which in effect was the government.

We asked the lab directly for comment and they said: ‘Ask RUSADA.’

We asked RUSADA and they said: ‘No comment’.

We asked the Russian ministry of sport and they said: ‘No comment.’

We asked Rodchenkov and he wouldn’t speak, and his sister said: ‘No comment.’

So then we put it all to the governing bodies concerned.

Official responses to Russian doping scandal, July 2013

IAAF: The IAAF is the global governing body of athletics. The president at the time was Lamine Diack. The world championships of the sport were imminent, to be hosted by Russia in Moscow. Seb Coe was one of four vice-presidents of the IAAF and not involved on a day-to-day basis.

We rang and emailed the IAAF several times to ask about what they knew. They did not respond to any call, or reply to any email, at all. They simply blanked us.

I tried a private direct approach to Coe’s long-term right-hand man, Nick Davies. He failed to respond, at all. Many months later he said he felt it wasn’t an IAAF issue but a WADA lab issue. Multiple people much closer to Davies than I’ve ever been swear passionately he would only ever act in the best interests of his sport and frankly I tend to believe them. He opted not to respond to serious allegations rather than address them, in the hope they might disappear until after the Moscow showcase event. In that regard, he was correct. Whether that was the best course of action in the long run still remains to be seen.

The IOC: On 2 July 2013, I emailed the IOC to tell them about the doping allegations in Russia. This email included the following: ‘The allegations are that officials are both selling drugs via doping programmes and ensuring positive results as a result are returned as negatives: this is where the lab comes in. We have also been told that whistle-blowers inside Russia have made these allegations directly to WADA and the IAAF. We know that the sister of the lab head, Grigory Rodchenkov, was imprisoned after supplying drugs to athletes. We have documents that appear to show Rodchenkov was also investigated over serious drug allegations related to the same case, and attempted suicide.’

We asked among other things if the IOC was aware of this, and whether the IOC had confidence in the lab.

On 3 July the IOC replied it was not ‘not aware of any investigation or prosecution of lab personnel.’ They added:

‘Visiting experts from the IOC and WADA monitor the labs in Russia and we are confident in the ability of the anti-doping authorities there to deliver in 2014.’

There was also a long section about the IOC’s confidence in the 2014 Sochi anti-doping labs.

On 3 July, I asked a supplementary question for avoidance of doubt: ‘We have paperwork and there is documentary evidence that the lab director Grigory Rodchenkov was investigated for supplying drugs; that he made a suicide attempt and was sent to a psychiatric hospital; and that he is now back at work. This was after his sister was sent to prison for selling doping products and athletes. Russian authorities will not confirm if any active investigation remains open against Rodchenkov. Your answer appears to me to suggest you have no knowledge of the investigation into Rodchenkov, the director of the lab. Have I read that correctly? You don’t have any knowledge that investigation happened?’

The same day, the IOC responded:

The IOC has received no information that Grigory Rodchenkov supplied drugs, but we would of course look into any accusation should you provide us with evidence.’

On 4 July 2013, I responded to provide details, including: ‘Listed in the official computer database of the Moscow City Court is material showing a case was pursued against Grigory Rodchenkov under article 234 paragraph 3 of the Russian criminal code, which relates to the supply of illegal and banned drugs. The case number is #44y-0173-2012.

‘No authority in Russia will comment on the case but our sources allege the case remains open. Nobody will discuss it publicly or comment on it. Our story revolves around this information: the fact of Rodchenkov’s sister’s conviction; the fact of an investigation into him; and testimony of several Russian athletes and coaches who say he was implicated in doping and cover-ups.’

On 5 July 2013, the IOC replied:

‘Hello Nick, Thank you for sharing with us this information. We have passed it on internally to the relevant people and we will get back to you as soon as we get a response. We apologise for this delay, but we have just ended a week of very important meetings and events. Many thanks for your understanding and best regards.’

And that was the last we heard from the IOC.

WADA: I first contacted WADA about this investigation towards the end of June 2013 to give them a ‘heads-up’ on the case and check one key fact – whether in fact our whistle-blowers had contacted WADA directly, as they had claimed. This could be pivotal to getting our story into print.

Without boring you with the details of journalistic process, stories of this nature as a matter of course must pass through the hands of teams of lawyers before being cleared to print. They need to be demonstrably true, in other words. They need evidence, and a right of reply. They need to ‘stand up.’

With the IAAF silent and the IOC ignorant, there remained the theoretical chance that our whistle-blowers and witnesses were making it all up, and that all the court papers and other evidence about Rodchenkov was merely the stuff of spy novels. We needed some second-source corroboration.

I called various people at WADA and then emailed on 27 June 2013. I stressed that the information in our possession ‘has potentially huge ramifications if information being passed to us is true.’

I outlined the claims and said I was seeking confirmation that WADA had separately been approached about this matter as early as 2012, in writing, by Russians wanting to air concerns.

Around the same time, another source in Russia came forward to us, on condition of anonymity, and claimed that WADA – specifically three named WADA officials – had not only been told about Russian doping in 2012, but also been informed that Rodchenkov was party to the conspiracy.

On 2 July 2013, I emailed WADA again, writing: ‘I have one further question arising from one further piece of information we have received.

‘The allegations we’re looking at concern doping in Russia but also alleged corruption relating to the Moscow lab where athletics world champ 2013 and Sochi 2014 samples will be tested. These include allegations of malpractice and sample tampering to show doping athletes as clean. The head of the lab Grigory Rodchenkov is implicated.

‘The new info today is a claim to us that specific individuals within WADA have been alerted that there is a problem with Russian doping, and the lab is implicated. Those who know of these allegations, we are told, are Olivier Rabin, Rune Andersen and John Fahey.

‘Could you confirm whether these individuals have been informed of these specific allegations, and whether WADA is actively investigating? Also, what power if any does WADA have to investigate such claims?’

The next day, 3 July 2013, WADA responded:

‘As previously indicated, WADA cannot comment on specific allegations. What we can say is that as the global organisation tasked with monitoring the fight against doping in sport, we undertake appropriate enquiries upon receipt of any information or allegations about doping, and then share it with the organisations that do have a mandate to investigate the situation fully.

‘Under the existing Code, WADA does not have the power itself to carry out investigations into allegations of doping. However, one of the planned changes to the 2015 Code is to grant WADA investigative powers. This would be a positive step forward in the global fight against doping in sport.’

I responded to that by asking WADA to tell me the appropriate body to which information could be passed for investigation, if not them. I explained RUSADA, the lab and the Russian sports ministry had all said: ‘No comment.’

WADA replied:

‘Hi Nick. Perhaps try contacting the country’s national anti-doping agency RUSADA.’

I was given a direct email address for RUSADA chief General Ramil Khabriev, who did not reply.

In summary: almost two months of investigative work established beyond what seemed to be reasonable doubt that there was a state-sponsored doping programme in Russia, centred around a corrupt lab where the director had been arrested and then released to do his work. Furnished with these details and with corroborating evidence and offers of further assistance, the IAAF ignored us, the IOC said they’d come back to us and never did, and WADA said it wasn’t in their remit to act.

The response

The story appeared and at different points later in 2013, the Mail on Sunday did follow-ups and nobody else did anything. That isn’t to criticise fellow media. I’m well aware this was, certainly then, an esoteric story and difficult to do as a ‘pick-up’ without the original sources and material, especially when it was presented ‘straight’ and not with front-page hyped bullshit claims employed by some other Sunday papers’ doping stories in recent years.

Russia responded by denouncing the story as western politically-driven propaganda, ignoring the fact that every key source was a Russian sick of institutional cheating.

Seventeen months after our story, the brilliant German investigative journalist Hajo Seppelt – a friend of mine, respected colleague and collaborator in some previous work – fronted his own investigation on ARD TV, taking the story on by some margin, implicating Diack in a cover-up. Covert filming of wrong-doers lifted the issue to global prominence in a way print perhaps cannot do. Hajo said he’d been unaware of our 2013 story, and no doubt he was. When the authorities successfully killed the original expose by failing to act, it died a death originally. Such is journalistic life at times.

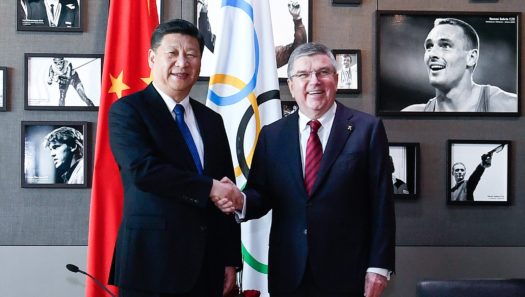

Scandals that sit in plain sight can go on for years or even decades without being resolved; we know that. The bribe-based award of the 2018 and 2022 World Cups to Russia and Qatar is one example; so too the corruption in FIFA from multi-billion ticket fraud over decades, the behaviour of countless senior officials, the buying and selling of elections and the conduct of dodgy ExCo members like Sheikh Ahmad Al-Sabah of Kuwait – one of the world’s most significant sports power brokers, who, incidentally, got Thomas Bach elected as IOC president in 2013.

Al-Sabah now effectively controls many of world sport’s governing bodies, directly and indirectly, who will now allow Russia to compete in Rio 2016. He’s a close pal of Bach, and Putin, and the Venn diagram of IOC-FIFA-political-dodgepots gets ever more crowded.

Another name in that group is Craig Reedie, president of WADA, and an IOC member, and deeply conflicted in ways he fails comprehensively to grasp. Why on earth anyone thought a doddery, confused chummy sports politician was the right man to head WADA was a good choice – heaven knows.

But only last year we reported how he was writing a ‘comfort’ letter to Russia to tell them, in effect, not to be too concerned about ARD and media focus on historic Russian doping. He said WADA wouldn’t do anything to upset his friendship with Russian sports minister Vitaly Mutko. And, thanks to all his IOC chums, he was right.

The 2016 Rio Olympic Games begin on 5 August.

Enjoy.

POST-SCRIPT, added on Saturday 30 July 2016

Since the publication of this piece on Monday, former WADA high-ups have admitted they should have taken action back in 2013, in a piece in The Australian.

It has also come to my attention that WADA, for technical reasons, have changed the version of the McLaren report available online. The new version at that link omits a letter that Rodchenkov sent to the Russian secret services in January 2015 to explain the contents of ARD’s programme in December 2014.

I mention this because the switch led me to review the original version of the McLaren report and re-read that letter. And I noticed something I had not noticed before – that Rodchenkov effectively admits within that letter that he and the Russia doping scandal were rumbled by our Mail on Sunday report in 2013.

How so? Well, if it weren’t so serious it would be comical.

As the McLaren report details, Rodchenkov had to write a briefing note to the Russian secret services in January 2015 about the whole scandal, and then Russian sports minister Vitaly Mutko later called in Rodchenkov to discuss the matter with him (showing this did indeed go to the top of Russian politics, way back).

It is Rodchenkov’s paragraph about the ‘origins of this scandal’, ie the origins of the exposure of the scandal, that are now revealing, not to mention hilarious. Rodchenkov told the FSB the origins (of the exposure) lay in the ‘working together’ of a man called Alexander Chebotarev and someone called Melkon Charchoglyan. The relevant passage is here:

![In general, the origins of this scandal and the film lie in the "working together" [of] Alexander Chebotarev and [Melkon Charchoglyan]...](https://www.jensweinreich.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/rodchenkov-letter-excerpt.png)

So who are Chebotarev and Charchoglyan?

Chebotarev is a lawyer who worked with Russian athletes including a series of whistleblowers and was indeed among some our of sources. So Rodchenkov is right there.

And Melkon was the work experience intern asterisked higher up in the piece! He was on a short summer placement at the MoS, having finished school, and was exceptionally helpful because he spoke, read and wrote fluent Russia. Hence he was able to assist us with some emails and calls in the language most comfortable to most of our sources, including Chebotarev.

I have spoken to Melkon this morning, Saturday, to let him know about his mention in the McLaren report. He thinks it’s a hoot. ‘I think Rodchenkov has overblown my involvement,’ he laughed.

Perhaps. Or perhaps not.

Neu: Olympia-Pass buchen! Recherche finanzieren.

In diesem Theater bekommen Sie auch heute wieder erstklassige Informationen, orientiert an Dokumenten, verbunden mit Analyse. Dieser Beitrag ist wie die Texte der vergangenen Tage, regelmäßig mit Exklusivmaterial versehen, bereits Teil meiner vorolympischen Berichterstattung. Einige Beiträge und Supplements werden hinter einer bescheidenen Paywall verschwinden.

Ich werde vom 1. bis 21. August, in hoffentlich alter Frische und bester Tradition, nahe an 24/7 aus Rio de Janeiro bloggen – wie zu anderen Großereignissen und während vieler anderer Reisen.

Das ist gerade die richtige, schwer durchschaubare Krisen-Atmosphäre für so ein Projekt. Für die sogenannte olympische Bewegung geht es ums Überleben.

An Ideen und Lust mangelt es nicht, ich bin in einem magischen olympischen Dreieck zwischen IOC, Deutschem Haus und Olympiapark in Barra da Tijuca einquartiert, erlebe meine 25. IOC-Session, wenn ich richtig zähle, habe als einer von nur wenigen Dutzend Journalisten weltweit Zugang zum IOC-Hotel, werde die Olympia-Bosse beobachten, interviewen, debattieren, werde recherchieren und Ihnen/Euch darüber aus erster Hand berichten. Ich freue mich sogar auf das traditionelle Live-Blog von der Eröffnungsfeier im João-Havelange-Stadion und den Kollegen G neben mir. Ob die Kraft reicht, muss der olympische Geist entscheiden.

- Sie können gern dabei sein und meine Art von Recherchejournalismus unterstützen.

- Im Shop gibt es den Olympia-Pass, sogar einen Jahrespass und andere journalistische Produkte.

Sagen Sie es gern weiter.

Pingback: Was vom Tage übrig bleibt (103): die Lügenwelt des ehrenwerten IAAF-Lords Sebastian Coe • Sport and Politics